Catholic Medical Quarterly Volume 66(4) November 2016

Mercy in Action: The Parable of The Good Samaritan

Luke Macnamara OSB

This

parable is perhaps one of the best known passages in the whole Bible. A

key concept from the parable has made it into medico-legal practice (the

Good Samaritan clause) whereby doctors are indemnified if they provide

assistance when they come upon an emergency. The Samaritans and many other

caritative institutions draw upon the image of the “Good Samaritan”.

This

parable is perhaps one of the best known passages in the whole Bible. A

key concept from the parable has made it into medico-legal practice (the

Good Samaritan clause) whereby doctors are indemnified if they provide

assistance when they come upon an emergency. The Samaritans and many other

caritative institutions draw upon the image of the “Good Samaritan”.

There is a great difficulty in reading a story which is so well known. Preconceptions lessen surprise and affect understanding. Every story is designed to entice a first-time reader. Like those who go to the theatre, or to the cinema, readers temporarily leave their own world and their own regular preoccupations and are drawn into a new world, with a new set of relationships and challenges – the world of the story. Jesus, as a capable teacher, often invites his audience to inhabit the story world of a parable which sets up situations of challenge, which incite his hearers to formulate their own responses.

The aim of this short essay is to enter, as if reading for the first time, the story of the meeting of Jesus and the lawyer and the parable Jesus later recounts to him. The lawyer is a professional person and might as easily be a doctor. Without doing violence to the story, it is proposed to identify Jesus' interlocutor as a doctor. Just then a doctor stood up to test Jesus. “Teacher,” he said, “what must I accomplish to inherit eternal life?” (Lk 10:25) The question has an ulterior motive. The doctor is testing Jesus, much as Satan and the Pharisees have done in the Gospel. The reader begins to be distanced from this doctor. However, the question asked is universally appropriate: “What must I accomplish to inherit eternal life?” It concerns all humanity.

Jesus in reply says: “What is written in the law? How do you read?” (Lk 10:26) The doctor responds: “You shall love the Lord your God with all your heart, and with all your soul, and with all your strength, and with all your mind; and your neighbour as yourself.” (Lk 10:27) The doctor gives a summary of the two basic tenets of the Jewish Law: love of God (Deut 6:5) and love of neighbour (Lev 19:18). He should get a good grade in his written exam. The reply of Jesus acknowledges this –“You have given the right answer”, but Jesus adds a condition. The code is not only to be known but to be put into practice. Jesus says “Do this and you will live”. Unlike the question, which spoke of what had to be accomplished to attain eternal life, the command of Jesus' reply is a present imperative implying a constant action. The supreme love of which the doctor has spoken is not a task to be done and then ticked off, but one that is to be lived every day.

The doctor is not ready to take the leap to clinical practice and wants to be viewed as righteous before examining a patient. Many in the Gospel (Pharisees, lawyers and scribes) seek to be well-perceived by others. Jesus repeatedly challenges these groups to stop parading about and instead help others, especially those in need. There is an increasing doubt about this doctor, so focused on prestige and reputation. The question he now asks is curious: “Who is my neighbour?” It implicitly begets another question “Who is not my neighbour?” The doctor seeks to limit the command of the law he cited so recently. As the doctor attempted to put a limit on the duration of care, (when can I be said to have done enough?) so now the limit is applied to the number of potential recipients of care:

- Who qualifies to enter the ambit of care?

- Who can be legitimately disqualified?

Jesus replies by inviting the doctor to enter into the story world of a

parable. “A man was going down from Jerusalem to Jericho, and

fell into the hands of robbers, who stripped him, beat him, and went away,

leaving him half dead.” (Lk 10:30) The nameless man's abject

condition elicits the reader's sympathy. Isolated and vulnerable to

further attack, his implicit question is “who will help me?” Continuing

the medical paradigm, the Priest and Levite of the story will be replaced

by a surgeon and physician. “Now by chance a surgeon was going down that

road; and when he saw him, he passed by on the other side. So likewise a

physician, when he came to the place and saw him, passed by on the other

side.” (Lk 10:31-32)

It is worth examining these scenes from the

perspective of each of the characters. The wounded man hears steps on the

road. His hopes rise with the steady cadence and until through his swollen

eyes he sees a man in scrubs with a surgical bag, but then they are dashed

as the man passes by. Again there are approaching steps and through his

eyes he glimpses a stethoscope dangling from a man's neck, but he too

turns aside. The surgeon and physician observe the man on the roadside. He

is a mess and near death. Both are out of their milieu and unlikely to be

able to do much. This will do the clinical audit figures no good. In

addition there is a risk that they might become victims of the robbers who

may not be far away. The question “what might happen to me if I stay?” is

a real one. The best thing is to press on to the next clinic.

The parable of course speaks of a Priest and a Levite who traditionally form a triad in Jewish parables with the Israelite, a regular member of the praying assembly of Israel. In keeping with the medical triad, the comparison here, of surgeon and physician might be completed by the general practitioner, who should be most attuned to spotting the injured man and arranging for care. The Jewish lawyer expects an Israelite to appear and be the hero, much as the doctor might expect the general practitioner to be the hero of the hour. However, the expected hero does not emerge.

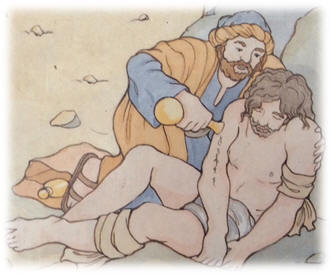

But a Samaritan while traveling came near him; and when he saw him, he was moved with pity. (Lk 10:33) The next traveller is identified as a Samaritan, a member of a neighbouring but enemy people who represent the most hated group for the Jews. The Samaritan is an anti-hero for the Jewish audience of Jesus and he may yet be the final villain of the parable and finish the wounded man off. Instead, when he observes the man, he is moved to pity. The Samaritan doesn't ask himself the question “what might happen to me?” Instead he asks: “What might happen to the wounded man?” The plight of the wounded man is uppermost in his thoughts and the real risk that he might die.

He went to him and bandaged his wounds, having poured oil and wine on them. Then he put him on his own animal, brought him to an inn, and took care of him. (Lk 10:34) The wounded man perceives that this third traveller is now beside him. Previously isolated, he now has someone to speak to, someone to tell his story to. The repeated experience of exclusion by the other travellers is now reversed.

The storyteller places greater emphasis on the Samaritan. Having been moved to pity, he is now moved to act. He makes contact with the wounded man and in forging a relationship takes on the associated responsibilities. He realises the seriousness of the man's condition and uses oil and wine, two costly items, to help heal the man. The Samaritan lifts the injured man onto his mount, brings him to the inn and works with others to bring the injured man back to health. The exclusionary practices of the first two travellers are contrasted with the search for restored communion for the invalided man, but also the communal manner of that restoration. The next day he took out two denarii, gave them to the innkeeper, and said, ‘Take care of him; and when I come back, I will repay you whatever more you spend.’ (Lk 10:35) The Samaritan cannot prolong his stay and so entrusts the wounded man to the innkeeper. He pays out the equivalent of two days' wages for the cost of the man's care and gives the innkeeper a blank cheque with regard to future care costs.

“Which of these three, do you think, was a neighbour to the man who fell into the hands of the robbers?” (Lk 10:36) Jesus and of being in receipt of care from another. This is not a perspective that comes easy to doctors who spend a lifetime focused on treating patients and yet all become patients at some point in their lives. Indeed experiencing illness and patienthood may be a transforming experience.

In fact Jesus' change of perspective is fundamental for all. The great attention given to every action of the Samaritan takes on new significance. These actions are not performed by an alter ego, rather these actions are directed towards the reader who is now made to identify with the wounded man. It is the position of an unglamorous underdog, with ugly wounds and bruises, but it is truly reflective of some readers and of all readers at some point in their lives. Jesus connects with his listeners at their most vulnerable.

He said, “The one doing mercy for him.” Jesus said to him, “Go and do likewise.” (Luke 10:37) The doctor, unable to pronounce the hated nationality of the Samaritan, identifies him as the one doing mercy for the wounded man. My neighbour is the one who does mercy for me. Neighbourliness is a two-way process and involves receiving as much as giving. The love of neighbour is to be enacted through the practice of mercy in the same manner as the Samaritan, but first the doctor is to be aware of all that he has received from others. This is the grounding experience from which his own care and giving emanates. The key ingredient in both directions is mercy not as a feeling or attitude but as a fundamental disposition that comes to expression in actions. There is a great truth in this story. All are travellers on the road. In life all will share the position of the wounded man at some stage and all will potentially share that of the Samaritan.

Luke Macnamara OSB

This paper is a modified version of a presentation given at the Irish Catholic Doctors Learning Network, 28 May 2016.