Catholic Medical Quarterly Volume 65(3) August 2015

Faith in Medicine

MICROCEPHALY AND A TALE OF TWO ENTITIES:

THE STORY OF CAMILLE MARYSE MCCLYMONT

JANUARY 1991- 28TH SEPTEMBER

2013

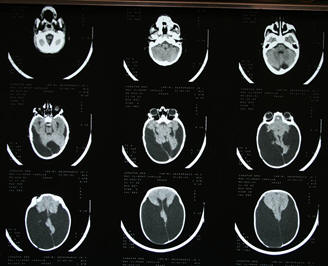

Camille Maryse McClymont, 22, who was born in Paisley, suffered from severe microcephaly. Her CT scans are reproduced below. She died in 2013 but her spirit inspired the development of a facility for adults with disablities in France and a care home in Cornwall - both of which have been named after her in tribute.

Camille, who lived in Brunswick Street in the city centre, moved to Cornwall with her family when she was five so that she could go to a specialist school. Her father William McClymont, 67, an art director and writer who is originally from Govan, said: "Camille's personality was infectious. People were drawn to her. She was a remarkable young woman." Mr McClymont added: "We were told at sixmonths- old that she wouldn't live to see her first birthday. "She did. Then her second, fifth, 10th and 20th.

We publish this story for several reasons. Firstly because it is a wondferful description of the humanity of someone who was severely disabled. And secondly because we know that so many children such as Camille are aborted or allowed to die as parents are told that microcephaly is incompible with life. The McClymonts have done us a great favour by showing what a person with severe microcephaly can bring with them.

As Dickens said, “It was the best of times, it was the worst of times,” and he was right. Camille, who was quadriplegic, blind and with no gag reflex and had severe cerebral palsy, inspired not only everyone who knew her, but two care homes in her name.

These were Camille’s Nest in Cornwall, and La Maison de Camille, in the

medieval village of Sauveterre de Guyenne, near Bordeaux, where we had

bought a house just before she was born. She was highly intelligent and

understood two languages and despite her restrictions, at the time of her

death, two of her carers were assisting her to write her book, due for

publication in 2015, with all the content from her.

These were Camille’s Nest in Cornwall, and La Maison de Camille, in the

medieval village of Sauveterre de Guyenne, near Bordeaux, where we had

bought a house just before she was born. She was highly intelligent and

understood two languages and despite her restrictions, at the time of her

death, two of her carers were assisting her to write her book, due for

publication in 2015, with all the content from her.

At six months old, while on holiday, she had life saving brain surgery at L’Hôpital des Enfants in Bordeaux and given a prognosis of zero. The doctor said, “Take her home and give her lots of love and affection, for there is nothing else”. So, we did and she thrived on it. Later, a French priest gave her the last rites and baptised her in the dining room of the house at seven o’clock one morning.

French doctors gave her the best care and treatment possible and saved her life, after which we returned to Glasgow where a specialist informed us facilely that she would not see her first birthday. She did, and her second, and her fifth and then her tenth. A teenager was now in sight and then a young woman. The advice given in Glasgow was different, it was in fact not to treat her, but to “let nature take its course”. Doctors in Bordeaux had worked so hard to keep her alive, and in Scotland, a specialist doctor and our “family GP”, a woman no less, not only saw no value in Camille’s life, but also had no respect for the efforts of their French contemporaries.

At L’Hôpital des Enfants in Bordeaux we were asked for her “Carnet de Santé”. Not only did we not have one, we had no idea what it was. “What were you told about her condition?” we were asked. “Nothing!” we said, to their disbelief. “But the doctors must have said something,” they went on, “they must have known, or how could they call themselves doctors?”

However, by comparison, in Glasgow, despite repeated complaints about Camille’s persistent distinctive crying, “le crie de chat”, as it is known in French, or sometimes “le crie de mouette,” cry of the seagull, we were told nothing. It was a policy of “deny everything, admit nothing.” We were told only that, “She is small but perfect,” or, “She IS an angry baby.” Scottish doctors, who knew us well, knew we were moving to France and let us go, as someone said, “with a time bomb”.

So, to the Carnet de Santé. It was as if we had come from some backward third world country. Of course, it’s the patient’s health record as a book that they keep to take with them each time they visit a doctor. It’s simple, easy, economical and accurate. Each doctor they see writes in it what they did, prescribed, or suggested, the patient always has an up to date record for the next doctor. In France, you do not register with a GP, you go to see any doctor you wish, so if you do not agree with this one, you take your Carnet de Santé and see another one, who of course they will know that you have been seen another one before, but that’s your prerogative.

French doctors were aghast at our ignorance for two reasons. Firstly, they expected to find Camille’s medical history readily available in the Carnet de Santé. Secondly, they could not grasp the concept that in this day and age, that in the UK, to the patient, their own health records are “Top Secret” with Stasiesque style of administration to keep them in ignorance. Why would any open administration behave like this? Could it be because as Camille was 3lbs 12ozs at birth and the pregnancy was totally mismanaged resulting in a caesarean section and the obstetrician declaring in a clinic in front of people, “I can’t tell the age of this foetus, I wash my hands of it”? So with a disaster of a pregnancy followed by six months of doctors avoiding answering questions, we had nothing tangible to offer to the French doctors.

However, a second opinion threw some light on it, a French opinion

based on hard facts. The reason Camille required the shunt was that she

now had hydrocephalus. The rate of leakage was measured against the total

fluid drained. When compared, it went back to the point of birth. Of

course, in Paisley, where Camille was born, all knowledge of any incidents

was denied. In Glasgow, where we had moved to and she was then being

treated, it was the same. In France we were informed that she had

microcephaly. Later in Glasgow, a dubious diagnosis of open-lipped

schizencephaly was mooted as the opinion of one man, but never verified.

It was convenient for a number of contentious reasons.

However, a second opinion threw some light on it, a French opinion

based on hard facts. The reason Camille required the shunt was that she

now had hydrocephalus. The rate of leakage was measured against the total

fluid drained. When compared, it went back to the point of birth. Of

course, in Paisley, where Camille was born, all knowledge of any incidents

was denied. In Glasgow, where we had moved to and she was then being

treated, it was the same. In France we were informed that she had

microcephaly. Later in Glasgow, a dubious diagnosis of open-lipped

schizencephaly was mooted as the opinion of one man, but never verified.

It was convenient for a number of contentious reasons.

The Royal Alexandra Hospital in Paisley strongly denied there was anything out of the ordinary during the birth. Incongruously, this same hospital, at the time they were denying this, also informed L’Hôpital des Enfants in Bordeaux that during the birth, Camille suffered from hypoxia. I include a copy of a brain scan taken just before the shunt was put in. So, this answers the question by the French doctors of what exactly did the Scottish doctors know? Well, everything! However, as our original GP in Paisley put it, “No doctor will shop another doctor.”

That was in the beginning, how much different would the end of the story be? Sadly, Camille did not manage to see the realisation of La Maison de Camille that she dearly believed in. In March of 2013 she became very ill with a recurrent problem, and in the wisdom of the day while in hospital, was put on LCP unknown to her family or her own team. Ironically this was at a point when she was at her best apart from the recurring abdominal problem. However, other people had other wisdom that prevailed and had the LCP reversed.

In August, while on holiday she again was ill with the same untreated abdominal problem, but this time her condition deteriorated further. A peculiar rigmarole ensued whereby a series of daily meetings took place. We would be taken to a side room, where each day a different doctor and a corroborating witness who never spoke, would conduct the same routine where they would explain that as they did not know Camille, could we tell them what we understand about the situation?

How did we see it? So there was a point to this daily routine, but no doctor ever offered how he saw it or disclosed the real point. You could see they were desperate to know what we thought, but would never say why or get to the point. Each meeting would fizzle out to be repeated the next day. It was a wearing down process, as they knew that to all intents and purposes, Camille was already dead. I could feel the tension and frustration mounting and eventually after five days one consultant had enough and came to the crux of the matter. He pointed out that, “normally in these situations, parents eventually realise that there is no hope and begin to discuss organ donation, have you considered this? We could have a surgical team on standby.” It was then the penny dropped, “So that’s what all this is about!”

A decision was made that the ventilator should be switched off and a time was set for the next day at one o’clock. Just like that, just like visiting the dentist or taking your car in for an MOT. It was as soulless as that. But this was our daughter coming to an end, not an old car bound for the knacker’s yard. Twenty odd years of her suffering and everyone’s effort and sacrifice terminated at the throw of a switch, like turning off the lights. So, after nine days in intensive care the ventilator was turned off and we waited for the inevitable, while the doctors waited for her organs, but we declined this. However, Camille being Camille, did not stop breathing soon after as expected, and so, next day, as nothing had changed, we took her home. She still needed her organs. Two and a half weeks later, she died very peacefully in her own bed, in her own room, surrounded by her favourite things and favourite people, in her treasured house, Camille’s Nest.

Meanwhile in France, Monsieur d’Amécourt, the local mayor, enlisted various French organisations, particularly Soliance and ESAT to find the funding to transform the house into eight apartments. It took four years before it all fell into place. Camille came to the meeting at the notaire’s in Sauveterre. She was listening proudly as it was decided that they would call the house, “La Maison de Camille”. As Madame Helena Alla, the Directrice of Soliance later put it, “Her name is symbolic to the project and will be on the building for a minimum of 55 years. She is an historic young woman and will always be significant in the town”. So, on Wednesday 15th January 2014, one well-loved person was conspicuous by her absence for the inauguration of the thousand year old newly restored church in Le Puch and La Maison deCamille. Firstly, mass was said in the church to bless the project before everyone decanted to the house to gather for the second inauguration. The affable, Monsieur Yves d’Amécourt was there with other mayors from local towns, the sub-prefecture from nearby Langon, the auxiliary Bishop from Bordeaux, various directors of the organisations, local councillors, even the head of the local gendarmerie was there, as well as many of the local disabled community. Camille’s mother, Dolly, and I, her father, represented her. This was a true community undertaking for the benefit of the town and with reverence to Camille, without whose approval, it would not have happened.

After this, everyone poured into their cars and a bus arrived to take the others to the village hall in Le Puch for the formalities, toasts and drinks. There were more than a hundred people there. They waited to see Camille, who was key to the event, but we could only hold back the tears and explain to everyone that she was not with us. Their disappointment at not seeing her was palpable. Many of them came to talk to us privately and offered their sympathy with sincerity. For La Famille MacClymont it was a very proud, though tearful day. It was valuable to all concerned as Camille’s memory is respected and esteemed in the history of this medieval village in Aquitaine where a warm heart and the value of human life is still cherished in this cynical age. The irony being that in the dark medieval days, the English built the town.

So this was how Camille was perceived in France, severely disabled, but a person, a vibrant, beautiful young lady who embraced adversity as part of her life and never complained, but appreciated the efforts of others who made her life work. She knew what it was to be disabled and jumped at the chance to help other disabled by agreeing for our house, the house that she knew as home, to be turned into apartments for local disabled young people to be in the centre of the town. This was next to the square, the hub of activity, with the town hall, the gendarmerie, the pharmacy and everything they needed, where a discreet eye could be kept on them and they were all looked after and live with independence and dignity. These were people, well respected as members of the community like Camille was. In Britain by contrast, she was a list of symptoms, a pile of case notes and letters of referral to various departments diligently administering her “care” through the politically correct paper work and her official rights. This was done with no heart, no soul, not an ounce of feeling but with callous indifference. In England for some, she was on an accounting sheet for money going out, for others, she was a revenue stream for money coming in, a commodity in a Kafka-esque NHS where protecting the NHS budget is the Holy Grail, but not protecting the NHS, which is being fragmented piece-meal.

This essential difference of the contrast of openness versus secrecy was to be, and still is, a major contentious aspect of our lives from August 1991 until the present, and with no sign of abating. In this respect, we could learn a lot from the French as well as their idea of what the point of being a doctor is. The value of the patient’s welfare comes before the cost. Doctors are concerned with the patients, not the accounts, that is other people’s business. Doctors are aware that in time, it may be their families, their parents or wives and children, and eventually themselves. It is humanity versus the balance sheet, the financial opportunity, the shareholders, it’s no contest if you are human and still have a soul to save, but it depends on the quality and value you put on life and what you believe a civilized society is.