Catholic Medical Quarterly Volume 63(3) August 2013

Book Review

Escaping the train from Auschwitz,

Catholics and

the Holocaust

Jim Curtis

Discussing

his survival in the Second World war, Simon Gronowski recently

said

Discussing

his survival in the Second World war, Simon Gronowski recently

said

"I want you to know that the most important words are 'peace' and 'friendship'. I speak to bear witness, to combat anti-Semitism, all forms of discrimination and Holocaust denial; to honour the dead and the heroes who saved my life - Jan Aerts, who risked certain death in protecting me, the Catholic families who hid me during the war, and my mother, the first of my heroes." [1]

His story is contained in a fascinating book [2], which sets an example for all Catholics in our daily lives

In 1943 an 11 year old boy called Simon Gronowski escaped from the only train from which Jews escaped during the second world war. They were rescued by three Belgian resistance fighters who ambushed his train with a red lantern and a pistol. Their lantern caused the driver to slow the train and after that the resistance fighters broke open doors of the train. In the end 233 tried to escape. Of that 233 people, 118 succeeded. 29 died from falling or gunshot wounds and the rest were recaptured. Simon Gronowski is now the only living witness

Simon had been arrested while having breakfast with his mother and his sister. Soon (but after a long period without food or water), they were taken and put on the train to Auschwitz.

Simon himself says he and many others had no idea they would be executed. In a train with no sanitation and no food or drink they set off on their unimaginable journey to death. But soon after the train left Gronowski’s convoy was attacked by the Belgian resistance. Robert Maistriau, one of the resistance members, wrote in his memoirs:

"The brakes made a hellish noise and at first I was petrified. But then I gave myself a jolt on the basis that if you have started something you should go through with it. I held my torch in my left hand and with my right, I had to busy myself with the pliers. I was very excited and it took far too long until I had cut through the wire that secured the bolts of the sliding door. I shone my torch into the carriage and pale and frightened faces stared back at me. I shouted Sortez Sortez! and then Schnell Schnell fliehen Sie! Quick, Quick, get out of here!"

At this stage Gronowski did not escape. After a brief shooting battle between the German train guards and the three Resistance members, the train started again.

But the actions of the resistance fighters drove others to seek to escape. After an hour, men in Simon's wagon succeeded in breaking open the door. Although he could not reach the foot-rail, his mother helped him down and eventually he was able to jump. "My mother held me by my shirt and my shoulders. But at first, I did not dare to jump because the train was going too fast for me," he says.

“But then at a certain moment, I felt the train slow down. I told my mother: 'Now I can jump.' She let me go and I jumped off. First I stood there frozen, I could see the train moving slowly forward - it was this large black mass in the dark, spewing steam."

But the train slowed to a stop for a second time that night and the German guards began shooting again, this time in Simon's direction. "I wanted to go back to my mother but the Germans were coming down the track towards me. I didn't decide what to do, it was a reflex. I tumbled down a small slope and just started running for the trees."

He walked and ran all night through woods and over fields. "I was used to the woods because I'd been in the cub scouts. I hummed ‘In the Mood’ to calm myself, which was a song my sister used to play on the piano," he says.

Simon wanted to get to Brussels and his father, Leon. But by the time day came he knew he must seek help. He knocked on a muddy village door and told the woman who answered that he had been playing with friends and got lost. Of course she was required to surrender him to the police. She knew that if she did not take Jews to the police she would be shot. So she took him to the local police officer and surrendered him.

Of course Simon expected then to be taken back to the Gestapo. But the Police officer, Jan Aerts, already aware of the escape, (he had three bodies already in the police station from it), had guessed Simon was from the Auschwitz convoy. Happily Jan Aerts decided to risk his life for Simon. He took him home to his wife who fed him and gave him clean clothes.

Jan Aerts then sent Simon back to Brussels. Back in Brussels Madeleine Rouffart (who had helped to arrange shelter for the Gronowski family before their arrest). She immediately took Simon to his father’s hideout at the Delsarts’ where he stayed from June 1943 until January 1944. Then he was moved to Henri Pieri and his wife Joséphine (née Calvaer), who sheltered him for eight months until the Liberation, as they had done before for others of Simon’s relatives.

Simon’s mother and sister both died at Auschwitz. Although all three of the resistance fighters were later captured, two survived concentration camps through to liberation.

Along with many others who sheltered Jews during the war, Jan Aerts, Madeleine Rouffart, Julia and Charles Delsart and Henri and Joséphine Pieri were declared "Righteous Gentiles" by the Yad Vashem museum in Jerusalem [3]. Leon Gronowski died within months of the end of the war. Simon Gronowski simply describes them as the “Catholic families who hid me during the war”.

Although he did not speak of his experiences for 50 years

Simon has now written a book. He recently told the BBC "I speak

about what happened to me so that you will protect freedom in

your country," he explains to children. "I want you to know that

the most important words are 'peace' and 'friendship'. I speak

to bear witness, to combat anti-Semitism, all forms of

discrimination and Holocaust denial; to honour the dead and the

heroes who saved my life - Jan Aerts, who risked certain death

in protecting me, the Catholic families who hid me during the

war, and my mother, the first of my heroes." [1]

“I speak to

bear witness, to …… the heroes who saved my life - Jan Aerts,

who risked certain death in protecting me, the Catholic families

who hid me during the war, and my mother, the first of my

heroes." [1]

This is therefore a beautiful story of escape and good Catholics risking their own lives to save others from death. Some may wonder why this is relevant to a Catholic Medical Journal. We submit that there are three good reasons to do this.

Firstly, we are aware that many Catholics died in the concentration camps and many of those were not of ethnic Jewish origin. St Maximillian Kolbe, Edith Stein and Blessed Karl Liesner (a seminarian who was later ordained in Dauchau) and many others died because they were Catholic and because of what they did. “Seattle Catholic” states that “according to the best estimate some 2,771 clergyman were inmates in Dachau. The largest number of clergyman were Catholic priests, seminarians, and lay brothers. A disproportionate number were the 1,780 Polish clergy, 780 of whom died in Dachau. Three thousand additional Polish priests were sent to other concentration camps. In addition, 780 priests died at Mauthausen, 300 at Sachsenhausen and 5,000 in Buchenwald. Many priests died shortly after they were liberated from Dachau and the other concentration camps — a direct result of the maltreatment and the illnesses that developed while they were interned. In addition, with the Nazi conquest of Western Europe, hundreds of priests were shot or shipped to concentration camps, many dying en route. Some priests were imprisoned because they read the Papal Encyclical “Mit Brendenner Sorge” in their Churches. Also many nuns were either imprisoned or shot. Dachau also served as the central camp for Christian religious prisoners.[4,5]

A huge proportion of all the priests and religious in Poland died in the Holocaust. In 1939, 80% of the Catholic clergy and five of the bishops of the Warthegau region had been deported to concentration camps. In Wroclaw, 49.2% of the clergy were dead; in Chelmno, 47.8%; in Lodz, 36.8 %; in Poznan, 31.1%. In the Warsaw diocese, 212 priests were killed; 92 were murdered in Wilno, 81 in Lwow, 30 in Kracow, thirteen in Kielce. Seminarians who were not killed were shipped off to Germany as forced labour.[6]

The Vatican and the Holy Father, Pius XII, took huge risks to protect Jews. Many more Catholics died because they sheltered Jews and others from the Holocaust. And yet, Catholics are never mentioned as victims of the Holocaust, never mentioned as victims of experimentation etc. We think that the frequently seen failure to make any mention of Catholics as victims is wrong. It might even be seen as a form of Holocaust denial. And we all know that the Holocaust was started by doctors who saw the economic efficiency of killing the disabled and elderly [7].

Secondly, Catholics died because our faith tells us that we should protect the innocent and vulnerable. Today, Catholics are called to protect the unborn and to speak out about bad medicine and medicine that kills others. The loss of 7 million babies in Britain since 1967 surely calls us to do all we can to protect innocent life. The protection of the unborn, the elderly and medical experimentation are all matters of great relevance to our journal.

Thirdly, as we seek the truth, we must applaud good men who do see that Catholics protect so many people so much of the time. While we would never deny the heinous crimes of abuse that have been documented about and by the Church, it is quite wrong that the very good things the Church and her members do are no longer reaching the mainstream media as they should. The Church is, after all, an enormous provider of excellent health care and teaching across the world.

For ourselves, we must remember to be brave and wise in all we do. Jan Aerts, the Pieri family and Mme Rouffart all risked their lives and that of their families to save a young Jewish boy. They were declared "Righteous Gentiles" by the Yad Vashem museum in Jerusalem. None of us risk death if we do what we can to protect the innocent, but we can put our careers and livelihoods at risk. The stories of Catholics in the Holocaust can be an example to us all.

References

- BBC news 20 April 2013 Escaping the train to Auschwitz By Althea Williams and Sarah Ehrlich http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/magazine-22188075

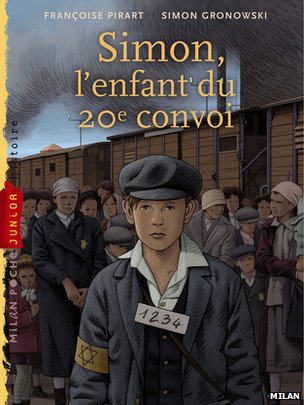

- Simon , l’enfant de 20e Convoi. Pirart and Gronowski. Pub Milan

- Yad Vashem museum. Madeleine Rouffart and Charles Delsart http://db.yadvashem.org/righteous/facebookFamily.html?language=en&itemId=4439087

- Gallo P. Dachaus priests. http://www.seattlecatholic.com/article_20030328.html

- Dachau concentration camp https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dachau_concentration_camp

- Thomas J. Craughwell. The Gentile Holocaust http://www.catholicculture.org/culture/library/view.cfm?recnum=472

- Saunders P. (2005) The Nazi Doctors Lessons from the Holocaust. Triple Helix Spring 2005, 6-7 http://www.cmf.org.uk/publications/content.asp?context=article&id=1606

Note, the book is in French, but very readable with moderately good French