Catholic Medical Quarterly Volume 62(4) November 2012

Humanae vitae: a legacy

Pia Matthews

Over forty years on, there is still plenty of talk about a

document concerned with contraception. Why? After all, many

priests report that issues of contraception do not come up in

the confessional. Certainly the Sacrament of Reconciliation as

individual confession is in deep crisis in many parishes and

this is so due to a number of factors. Arguably one significant

factor is that there appears to be a disconnection between

Church teaching and actual practice. And many point to the

practice of contraception as the chief culprit. Undoubtedly Pope

John Paul II’s famous Wednesday catechetical sessions and

subsequent book the Theology of the Body was written in part,

though only in part, to address this disconnection. However it

seems that the debate has moved beyond ‘responsible parenthood’,

not the least because the Church is seen as complicit in the HIV

AIDS tragedy in Africa by its refusal to accept the distribution

of condoms. The controversy surrounding Humanae vitae is as

alive as it was when Pope Paul VI first wrote his encyclical.

The answer perhaps is that Humanae vitae had, and still has,

repercussions for the Church even beyond its subject. In

particular it has implications in two specific areas: firstly

for moral theology in its method and subject matter and secondly

for Church authority and individual conscience.

Over forty years on, there is still plenty of talk about a

document concerned with contraception. Why? After all, many

priests report that issues of contraception do not come up in

the confessional. Certainly the Sacrament of Reconciliation as

individual confession is in deep crisis in many parishes and

this is so due to a number of factors. Arguably one significant

factor is that there appears to be a disconnection between

Church teaching and actual practice. And many point to the

practice of contraception as the chief culprit. Undoubtedly Pope

John Paul II’s famous Wednesday catechetical sessions and

subsequent book the Theology of the Body was written in part,

though only in part, to address this disconnection. However it

seems that the debate has moved beyond ‘responsible parenthood’,

not the least because the Church is seen as complicit in the HIV

AIDS tragedy in Africa by its refusal to accept the distribution

of condoms. The controversy surrounding Humanae vitae is as

alive as it was when Pope Paul VI first wrote his encyclical.

The answer perhaps is that Humanae vitae had, and still has,

repercussions for the Church even beyond its subject. In

particular it has implications in two specific areas: firstly

for moral theology in its method and subject matter and secondly

for Church authority and individual conscience.

Still it is useful perhaps to put the encyclical in context and perhaps the starting point can be found in the 1930s. In what was described at the time as a “bolt out of the blue” the Anglican community at its Lambeth Conference became the first Christian body to accept the use of artificial birth control within marriage. Commentators of the day noted that sociological and psychological pressures called for change and, to the surprise of many, it was said that Lambeth “jumped on the bandwagon”. The Conference clearly recognised that it was going against Christian tradition and the move was not unanimously supported: the vote was 193 in favour and 67 against. Moreover the change was not a ringing endorsement of contraception. According to the Conference’s Resolution 15 there had to be a “clearly felt moral obligation to limit or avoid parenthood”; it recognised that “the primary and obvious method” was complete abstinence “in a life of discipline and self-control lived in the power of the Holy Spirit”; it stressed that there had to be a “morally sound reason for avoiding complete abstinence” and the method must be decided on Christian principles. Moreover the Conference recorded its “strong condemnation of the use of any methods of conception control from motives of selfishness, luxury, or mere convenience” [1]. Underlying its departure from the Christian tradition the Conference took the view that what a couple did in marriage was a private matter.

This prompted a robust response from Pope Pius XI. In his

encyclical Casti connubii and addressing the issue of married

life in general not simply the issue of contraception Pope Pius

made it clear that marriage is not simply a private human

institution [2]. Rather it is divinely ordained for the good of

the spouses, children and society. It is a sacrament and,

quoting St Augustine, the goods of marriage are faithfulness,

children and unity [3]. Once the deliberate frustration of the

marriage act through artificial birth control is allowed then

children are no longer seen as one of the goods of marriage.

Instead they become one of its “disagreeable burdens” to quote

Pope Pius [4].

This prompted a robust response from Pope Pius XI. In his

encyclical Casti connubii and addressing the issue of married

life in general not simply the issue of contraception Pope Pius

made it clear that marriage is not simply a private human

institution [2]. Rather it is divinely ordained for the good of

the spouses, children and society. It is a sacrament and,

quoting St Augustine, the goods of marriage are faithfulness,

children and unity [3]. Once the deliberate frustration of the

marriage act through artificial birth control is allowed then

children are no longer seen as one of the goods of marriage.

Instead they become one of its “disagreeable burdens” to quote

Pope Pius [4].

Whereas the Lambeth decision of 1930 allowing contraception was a “bolt from the blue” some heralded the arrival of Humanae vitae thirty years later as a “chilling blast”. Humanae vitae reiterated traditional Christian teaching [5] and the philosopher Elizabeth Anscombe said that the point of the debate should not have been why Humanae vitae, but why the Lambeth statement.

Nevertheless, thirty years on from Lambeth the scene had changed. In the 1950s the chemical innovation of the pill that impeded ovulation before intercourse suggested to some that it could be seen as a natural form of contraception since it meant that couples could regulate fertility without having recourse to surgical intervention (sterilisation) seen as mutilation of a healthy organ and it did not interfere with the marital act itself. Moreover, the developing role of women in society, debate on the difficulties experienced by married couples and, in particular, fears of overpopulation indicated for some a need for a new debate.

Perhaps even more crucial, this was the era of the Second Vatican Council and Pope John XXIII’s vision for a Church that would look outwards to the modern world and be in dialogue with it through reflection on the ‘signs of the times’. There was certainly excitement and promise in this new venture: talk of the Church in the Modern World, rejuvenation of the liturgy, ecumenism, religious liberty, renewal of priesthood and religious life, reflection on the constitution of the Church and perhaps above all on the vocation of the laity led undoubtedly to a heightened sense of expectation. Arguably Humanae vitae became a ‘test case’ for interpreting the Second Vatican Council.

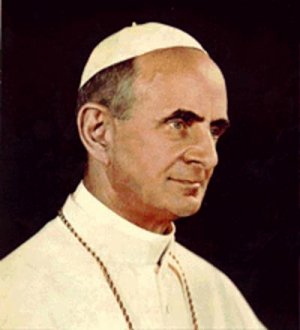

Out of this mixture of expectation and vision Pope Paul VI

came to write Humane vitae. However Pope Paul did not write ‘out

of the blue’. Pope John XXIII had already set up a confidential

commission to consider the threat of over-population in the

context of the constant tradition of the Church. The Second

Vatican Council document Gaudium et spes had already explained

the “lofty calling” of marriage [6], the self-giving of the

couple in “authentic married love caught up in divine love” and

their “generous fruitfulness” [7], the vocation to holiness that

is marriage. However it was recognised that detailed

investigation into marriage and the life of the “domestic

Church” was required.

Out of this mixture of expectation and vision Pope Paul VI

came to write Humane vitae. However Pope Paul did not write ‘out

of the blue’. Pope John XXIII had already set up a confidential

commission to consider the threat of over-population in the

context of the constant tradition of the Church. The Second

Vatican Council document Gaudium et spes had already explained

the “lofty calling” of marriage [6], the self-giving of the

couple in “authentic married love caught up in divine love” and

their “generous fruitfulness” [7], the vocation to holiness that

is marriage. However it was recognised that detailed

investigation into marriage and the life of the “domestic

Church” was required.

Pope Paul VI took up the challenge of the Second Vatican Council and the confidential commission carried on its work though debate surrounds its purpose and remit. Certainly Pope Paul was always clear that the commission was an advisory body and that is was his responsibility to make any final decisions in the light of Catholic tradition. Whilst he was considering the commission’s findings and its doctrinal and pastoral implications (and it has been suggested that the commission did indeed exceed its remit) the Commission’s report was leaked (under the title of the Majority Report) but it was not unanimous and another report (the Minority Report) was also produced.

Apparently after much agonising and mindful of the weight of responsibility because of the impassioned debates Pope Paul produced Humanae vitae, On the right ordering of propagating human offspring, in 1968. His dilemma, he said, was one of yielding to current opinion or delivering a judgment that would be ill-received or seen as an imposition. However he believed that there was a problem: certain approaches, and presumably he had in mind part of the Majority Report, were inconsistent with the Church’s firm traditional teaching. After prayer, reflection, consideration of the holiness of married life, pastoral sensitivity and the traditional teaching of the Church he finally felt he had a duty to speak and he prepared the encyclical in a spirit of hope. He accepted that his words might appear severe and difficult but he aimed at interpreting the genuineness of married love in the light of the love Christ has for his Church.

For the majority report the couple become the source of new life by their timing of the conjugal act: they become masters not minister, and this puts in jeopardy the vision of the child as a gift not as a burden.

It seems that according to the Majority Report as long as the marriage as a whole was open to children married couples could use artificial birth control methods (that did not cause abortions) since, the Report said, couples could not be condemned to long and often heroic abstinence. Whilst the Majority Report seemed to take the view that their request was slight only later was it felt that a change could mean that previous teaching was wrong (remembering that it was Lambeth that broke away from the constant Christian tradition) and a change in this would justify a change in all teachings of morality. For traditional moral theology the approach of the Majority Report was problematic in another area: it did not take into account each act. In traditional moral theology acts matter not because they are single fleeting events but because at the core of each act is my free choice and the choices I make make me into the person I am – acts shape us. If I do evil then I become evil and I am more likely to act in an evil way next time. That is why I cannot do evil hoping that good may come of it. Moreover for the Majority Report the couple become the source of new life by their timing of the conjugal act: they become masters not ministers, and this puts in jeopardy the vision of the child as a gift not as a burden.

For Pope Paul the inseparable connection between union and procreation is inherent in the marriage act as ordered by God [8]. Unlike many critical views of the traditional Catholic approach, sex is not ‘just for producing children’. It is also for the good of the spouses. Pope Paul continues, God wisely ordered nature and by its natural rhythms the act may be infertile at times but “constant doctrine” is that each and every marital act must retain its intrinsic relationship to procreation [9]: it must always be open to the possibility of the gift of new life. Contraception and natural family planning are not different methods to achieve the same result. They are different attitudes and behaviours, the former deliberately obstructs but the latter asks for respect and at times abstinence: to explain this Elizabeth Anscombe uses the analogy of sabotage and working to rule [5]. For love to be “fully human” and a matter of “free will” not pure instinct or drive [10] it requires self-control and respect. Using artificial birth control risks reducing the other partner, usually the woman, to a “mere instrument” [11]. Contraception risks making children into objects, an object out of the other, and indeed objectivising oneself.

Certainly Pope Paul was aware of the pastoral implications of his teaching and he recognised the need for support, compassion and education [12], and above all the need for grace and the sacraments [13]. However he is equally clear that the Church sometimes has a duty to be a “sign of contradiction” in the world [14]. What he was most concerned with, it seems, is the harm done to human dignity when we have a materialistic notion of human beings, when we do not think human beings can overcome their immediate desires or when the gift of new life is seen as a burden.

And the fall out?

Certainly the manner in which Pope Paul reserved judgment to himself, given the sense of collegiality of the Second Vatican Council is one issue yet to be worked out. Still, Pope Paul did ask bishops and priests to commend the teaching. But many felt he need not have taken the burden completely on himself. Pope Paul did not write another encyclical.

The failure of the encyclical’s reception among some theologians and laity had a more immediate impact, firstly on the nature of moral theology and secondly on Church authority and individual conscience.

Moral theology

There had already been calls for a renewal of moral theology prior to the Second Vatican Council and during the Council. The perceived problem was that moral teaching was based on moral philosophy not theology. Looking back at the history of moral theology there are several strands that affected its development. Exhortations, sermons and treatises of the early Church Fathers in response to particular pastoral issues were joined by the penitentials, books written originally in monastic communities, to encourage the practice of the virtues as medicine for vice. The Fourth Lateran Council’s recognition of the need for regular confession in the lives of Christians in 1215 led to the production of practical textbooks, manuals, to inform and support confessors. These texts at first reflected the then current scholastic method of presentation as illustrated by the works of St Thomas Aquinas where morality sits in between God and creation and then the Incarnation and sacraments, and the life of the world to come. But later developments, for instance the copying of only the moral section of the work of St Thomas took morality out of this context and away from a presentation of the moral life as living out the message of the Gospel. The focus began to turn on either condemning or excusing transgressions of the laws of God and the Church. Moreover, whilst the Council of Trent and in particular the Jesuits rightly encouraged a move towards deeper spiritual direction of the faithful, an unfortunate offshoot of this was that studies on the relations of divine law and liberty of conscience replaced the focus on grace and the gifts of the Holy Spirit. The result; an overly legalistic approach to moral theology.

Certainly the general atmosphere of the Second Vatican

Council had an impact on moral theology. The Second Vatican

Council called for a rediscovery of the roots of Christianity

and the Gospel message, an openness to renewal and criticism

through dialogue with other Christians and other faiths and it

urged a greater awareness of human experience. Above all it

called for moral theology to be more attentive to Scripture. To

some this may have suggested a time for change rather than

continuity in teaching.

The Majority Report, perhaps

inadvertently, pushed moral theology beyond renewal through

continuous deepening to radical change. It may be of interest to

note that Cardinal John Henry Newman characterised development

in Church tradition in terms of a stream that becomes a river

that grows ever deeper and not as making a dam and starting

again. Thus, Humanae vitae became a fracture point for moral

theology.

Pope Paul’s reiteration of the traditional condemnation of contraception, vociferous dissent from some prominent theologians and the failure of many lay faithful to accept his teaching led to two approaches to moral theology. The new revisionist approach aimed to reflect better what it saw as the actual experience of conscientious lay Catholics and at times it called for change. The more conservative renewal approach sought to deepen traditional teaching and make it more understandable and persuasive. Its mission was to present the reasoning and wisdom behind Church pronouncements. Both approaches showed that traditional moral theology had been found wanting and was in need of renewal.

Whilst the revisionists looked more to change than continuity in moral theology and the issue of contraception seemed to be an ideal case to argue for change, the debate has now moved on. Just as the Majority Report considered the whole of the marriage rather than individual marital acts, some revisionists question whether any act can be characterised as intrinsically wrong prior to consideration of its consequences. Those who once supported contraception but resisted abortion and homosexual practice now support these as well. Moreover the issue is not so much about contraception and responsible parenthood. After all, nowadays although the pill is still commonplace there is more interest in natural family planning methods as these are seen to be more human friendly and closer to promoting quality relationships as well as being free from chemicals and devices. Rather the issue has become the prevention of sexually transmitted diseases by condom use, even though many diseases cannot be prevented by anything other than abstinence, and the possibility of emergency contraception that may operate by impeding the implantation of an early embryo. If it is said that acts are merely neutral and it is how they fit into the totality of what people do including all the circumstances and the good reasons offered then it seems no longer possible to say that this act is, in itself, evil.

Pope John Paul II made a considerable contribution to the

debate not least because he was particularly interested in moral

theology. Moreover, whilst the term aggiornamento is often

translated simply as ‘bringing things up to date’ Pope John Paul

understood the dialogue envisaged by Pope John XXIII and

realised in the Second Vatican Council as being richer. The

concept of aggiornamento combines an understanding of renovatio,

a conservation and appreciation of basic elements, with

accommodata, accommodation to modern circumstances through

timely changes and innovations in non-essentials. In his

encyclicals Veritatis splendor, the Splendour of Truth written

in 1993 and Evangelium vitae, the Gospel of Life written in

1995, Pope John Paul’s principal encyclicals on moral theology,

the Pope recognises these new debates surrounding moral

absolutes and so contraception is not the focal point. Those who

once defended contraception now defend abortion and euthanasia

and so it is the moral absolute against the taking of innocent

human life that Pope John Paul makes explicit. Yes,

contraception is mentioned but Pope John Paul makes it clear

that it is not on the same level. Perhaps this is a clear

example of the dangers of the ‘slippery slope’, a danger that

cannot always be simply legislated against. A noteworthy

illustration of this might be emergency contraception. The

morning after pill is believed to work by making the environment

of the uterus hostile to the newly fertilised egg so that it

does not implant. But what is the newly fertilised egg? In the

court case brought by the Society for the Protection of the

Unborn Child SPUC argued that the morning after pill caused an

abortion and that therefore under the terms of the Abortion Act

it required the signatures of two doctors, so it could not be

prescribed over the counter at the chemist. The court decided

that pregnancy only begins at implantation and awarded such

punitive damages against SPUC that it could not go to appeal.

But consider now the couple undergoing IVF. Ask them whether

what is in the petri dish are just a collection of cells or

their embryos. For those who consider that acts are merely

neutral then taking the morning after pill in the light of all

the circumstances and for good reasons can make it into a good

or at least neutral act.

Pope John Paul II made a considerable contribution to the

debate not least because he was particularly interested in moral

theology. Moreover, whilst the term aggiornamento is often

translated simply as ‘bringing things up to date’ Pope John Paul

understood the dialogue envisaged by Pope John XXIII and

realised in the Second Vatican Council as being richer. The

concept of aggiornamento combines an understanding of renovatio,

a conservation and appreciation of basic elements, with

accommodata, accommodation to modern circumstances through

timely changes and innovations in non-essentials. In his

encyclicals Veritatis splendor, the Splendour of Truth written

in 1993 and Evangelium vitae, the Gospel of Life written in

1995, Pope John Paul’s principal encyclicals on moral theology,

the Pope recognises these new debates surrounding moral

absolutes and so contraception is not the focal point. Those who

once defended contraception now defend abortion and euthanasia

and so it is the moral absolute against the taking of innocent

human life that Pope John Paul makes explicit. Yes,

contraception is mentioned but Pope John Paul makes it clear

that it is not on the same level. Perhaps this is a clear

example of the dangers of the ‘slippery slope’, a danger that

cannot always be simply legislated against. A noteworthy

illustration of this might be emergency contraception. The

morning after pill is believed to work by making the environment

of the uterus hostile to the newly fertilised egg so that it

does not implant. But what is the newly fertilised egg? In the

court case brought by the Society for the Protection of the

Unborn Child SPUC argued that the morning after pill caused an

abortion and that therefore under the terms of the Abortion Act

it required the signatures of two doctors, so it could not be

prescribed over the counter at the chemist. The court decided

that pregnancy only begins at implantation and awarded such

punitive damages against SPUC that it could not go to appeal.

But consider now the couple undergoing IVF. Ask them whether

what is in the petri dish are just a collection of cells or

their embryos. For those who consider that acts are merely

neutral then taking the morning after pill in the light of all

the circumstances and for good reasons can make it into a good

or at least neutral act.

Pope John Paul does however seek to deepen the traditional view against contraception in Humane vitae through his Wednesday catechesis and his Theology of the Body where, starting from Scripture, and in particular the Book of Genesis he describes the human meaning of sexual union as “nuptial”, as a language spoken between the couple. And with this approach he follows the renewal rather than the revisionist approach to moral theology. Perhaps in contrast to Humanae vitae Pope John Paul’s encyclical on the role of the Christian family, Familiaris Consortio written in 1981 was formulated after the 1980 synod of bishops with representatives of lay groups and it includes much of the discussion made at the synod. This encyclical is not restricted to issues of contraception but it does stress that theologians should work to bring about the personalist and biblical foundations of the teaching of Humanae vitae. Although Pope John Paul accepts that he is teaching in a difficult context where there is anxiety and serious problems of responsible parenthood and population growth [15], love, he says, does not end with the couple [16]. Our culture is confused and distorts sexuality from its essential reference to the person [17]. The human person is not a sum of parts where we can remove fertility. Married love has a whole view of the person and involves total self-giving.

Church authority and individual conscience

Talk to some priests and their main concern over the aftermath of Humanae vitae is the crisis it provoked in Church authority. Unless we can deal with the unspoken contraceptive mentality, they say, what we preach from the pulpit will go unheeded. This, they feel, goes hand in hand with the collapse of the discipline of regular confession in the Sacrament of Reconciliation.

The impact of Humanae vitae on understandings of conscience offers profound reflection and needs deep exploration.

The impact of Humanae vitae on understandings of conscience offers profound reflection and needs deep exploration. Suffice it to say that in the tradition conscience is not seen in terms of a confrontational court of appeal where I become the final arbiter of what is true and good. To bring in Cardinal Newman: for Newman conscience is not the right to self-will [18]. Moreover authority and individual conscience are complementary. Conscience gives us a sense of right and wrong and it is Revelation through Scripture, Tradition and Magisterium, Church Teaching, that give us a sure guide [19]. Human beings have a duty to inform their consciences and deepen their understanding through thinking hard, honestly and practically, with also a certain humility. We are bound to follow our conscience if we believe that one line of action is what God expects of us. Finally, obedience even to an erring conscience is the way to gain light [20] for people must being their journey from where they are and as they travel they will eventually see the right path. After all the formation of conscience is a life-long task and we are always being called to inform our conscience by deepening our understanding.

And HIV AIDS?

Where does this leave us when we consider one of today’s

pressing issues, that of the HIV and AIDS pandemic exacerbated,

many argue, by the teaching of Humanae vitae? Is the Church’s

decision not to distribute condoms the result of myopia over

birth control and a fixation with controlling sexuality?

Pope John Paul and also Pope Benedict describe HIV and AIDS as

“one of the major catastrophes of our time” [21] and they

declare the need to fight against it. How do we engage in the

fight? We know that, most of all, the abstinence and be careful

components of health education in Eastern Africa have been

central to the response to the AIDs epidemic.

For Pope John Paul and Pope Benedict especially of concern is the lack of access to medical care for HIV AIDS patients and medical treatment to prevent its transmission from mother to child [21]. At the Fourth Vatican AIDS Conference 1989 Pope John Paul reissued the Church’s call to compassion and to solidarity and he reemphasised that AIDS prevention must be “worthy of the human person” and “truly effective”. Prevention that promotes “egotistic interests” does not, he says, resolve the problem at the roots. He calls for “responsible sexual behaviour” that includes self-control, respect for the whole of human life and a true love for the marriage partner. Both Popes demand an end to discrimination and the provision of total care for the sufferer and his or her family.

The debate has moved on. With Pope John Paul the criticism was that he did not condone the distribution of condoms and more condoms would save lives. Now it is recognised that simply supplying condoms does not solve the problem. Moreover the World Health Organisation says that of those who do use condoms consistent and correct use reduces the risk of HIV infection by 90%. The question remains, if a husband truly loves his wife would he risk a 10% chance of infecting her and possibly their future child with a devastating disease? Pope Benedict is accused not so much of refusing the distribution of condoms but of suggesting that promotion of condoms risks making the situation worse. Returning to Humanae vitae, Pope John Paul VI argued that four main problems would surface with the acceptance of artificial birth control: a general lowering of moral standards throughout society; a rise in infidelity; a lessening of respect for women by men; and the coercive use of reproductive technologies by governments. Certainly some countries are inclined to offer help with AIDS as long as it goes hand in hand with family planning. And who suffers most in Africa? As always it is the most vulnerable members of society, the women and children, who risk becoming objects for the more powerful.

References

- http://www.lambethconference.org/resolutions/1930/1930-15.cfm

- Casti Connubii. (1930) Encyclical of Pope Pius XI on Christian Marriage, http://www.vatican.va/holy_father/pius_xi/encyclicals/documents/hf_p-xi_enc_31121930_casti-connubii_en.html #37, #77, #86, #91

- #10, #41

- #53

- Elizabeth Anscombe outlines this constant tradition www.orthodoxytoday.org/articles/AnscombeChastity.php

- Gaudium et Spes. (1965) Promulgated by His Holiness, Pope Paul VI. Pastoral constitution on the church in the modern world. #47

- #48

- Humanae Vitae (1968). His Holiness Pope Paul VI. http://www.vatican.va/holy_father/paul_vi/encyclicals/documents/hf_p-vi_enc_25071968_humanae-vitae_en.html

- #11

- #9

- #17

- #19, #22

- #20, #25

- #18

- #30-31

- #14

- #32

- Cardinal John Henry Newman (1874) A Letter Addressed to the Duke of Norfolk on Occasion of Mr. Gladstone's Recent Expostulation Certain Difficulties Felt by Anglicans in Catholic Teaching, Volume 2 http://www.newmanreader.org/works/anglicans/volume2/gladstone/index.html

- Cardinal John Henry Newman (1845) An Essay on the Development of Christian Doctrine 86

- Cardinal John Henry Newman (1864) Apologia Pro Vita Sua p206

- Message of Pope John Paul II to the Secretary-General of the United Nations organisation 2 June 2001

- AVERT (2012) HIV and AIDS in Africa http://www.avert.org/hiv-aids-africa.htm

- AVERT (2012) Women, HIV and AIDS http://www.avert.org/women-hiv-aids.htm