This article appears in the August 1998 edition of the Catholic Medical Quarterly

Return to CMQ Aug 1998 Page

The cradle of the womb: take care who peeps in

Josephine Treloar

Introduction

I am writing this as a GP and a mother who has experienced at first hand the desire of ante-natal services to screen out and destroy children whom they consider to be unwanted. They are so keen to do this that they will actually do so without the consent or even knowledge of the mother. As Christians we are bound to be concerned about such moves. The joyful time of pregnancy can be a harsh and dangerous time. Mothers need all the support and knowledge they can get, to enable them to withstand some of the destructive pressures which are now inbuilt within the ante-natal care system.

Current public policy is increasingly designed to minimise expenditure on the care of the mentally or physically handicapped.1 The main legal way to do this at present is, of course, to prevent them being born alive. The dragnet is designed to be as comprehensive as possible and enrols all parents in screening, even though many of them only really want to see the scan of their baby (or babies) alive and confirm their dates. Although there are many good obstetricians and midwives who provide excellent care for mothers and their unborn, they are working within a system where, if a baby is born with an abnormality which could have been detected (and the baby aborted), they are open to law suits for "wrongful life". Courts in Britain have already awarded damages of tens of thousands of pounds to at least one mother who gave birth to a Down's syndrome child after failure to diagnose the child before birth.2

Tests currently performed

Alpha feto-protein

A test like the Alpha feto-protein (AFP) has been around for many years as a non-specific marker for conditions such as spina-bifida. More recently, it has been used in combination with some other blood tests and maternal age to produce a clearer assessment of the mother's "risk" of carrying ababy with Down's syndrome. These tests are usually performed at about 16 weeks. An abnormal result would be followed either by a detailed ultrasound, to clarify the presence of structural problems which could be visibly identified, or by amniocentesis. The straightforward AFP blood test is ' performed along with other blood tests which are also done at 16 weeks. Minimal explanation and consent from many mothers are not unusual. Obviously, more complex investigations usually require more informed consent from the mother. However, by now these mothers are very much on the "seek and destroy" conveyor belt. They are often out of their depth and tenified. 1 have seen women carried along by the enthusiasm of doctors and midwives to screen out and remove children who they think may be "defective". It is very hard for women to stand up to the pressures they experience in these situations.

The Nuchal translucency Test

It has now been decided, in many areas of the country, to perform an additional ultrasound test on all mothers at 11-13 weeks. Its main reason is to pick up many of those who show signs of being at increased risk of carrying a baby with Down's syndrome. It leads on to amniocentesis. Nuchal translucency is however a remarkably soft sign. It is associated with a variety of chromosomal defects as well as structural anomalies such as renal dysplasia and exompholos. When used for population screening only 5% of positive tests are associated with trisomy 21.3 Nuchal translucency will usually detect and then eliminate up to 70% of live children with Down's syndrome.4 All this for a condition associated with hardship for parents but children who are so often specially happy and loved.

Amniocentesis

Amniocentesis involves removing fluid from the amniotic (or fluid) sack around the foetus with a needle and syringe, usually under ultrasound guidance. It can be performed from 11 weeks (after the test period) but, because of 'unacceptably high losses', it is usually only performed after 16 weeks. The miscarriage rate following the procedure is 1 %, rising to 2% in excess of natural loss when performed as early as 11 weeks (1% of established 16 week pregnancies is actually a very high rate of loss)5. Amniocentesis was fairly disastrous for at least one older mother who had achieved her first pregnancy, was badgered into the test by the registrar, and subsequently lost her baby. Rarer side effects are the formation of silky fibrous bands across the amniotic sac around which the baby can wrap fingers, toes and even limbs - and thus be born without them.

Chorionic Villous sampling

Chorion Villous sampling, usually performed from 11 to 14 weeks aspirates placental tissue for testing, takes 2-3 weeks for a result and causes 1-2% foetal loss.

Obstetric ultrasound

Knowledge on gestation can be invaluable if intervention is required for the benefit of mother and/or baby. This is especially true when deciding when to deliver babies around 23-28 weeks. A baby with spina-bifida, treatable heart problem or an abdominal wall defect can undoubtedly fare better if delivered in an appropriate unit with specialist paediatric care rather than being transferred in an incubator for surgery.

Predictive validity of prenatal diagnosis

Many assume that amniocentesis is essentially a "gold standard" technique which gives 100% diagnostic certainty. One interesting report from Denmark has questioned this statement. Denmark is the only country where the national cytogenetic laboratory aims to follow up the results by either analysing the genetics of the born child or the miscarried or aborted baby. They found that one third of babies diagnosed as being chromosomally abnormal with Turner's syndrome who were not aborted, turned out to be normal.6 Perhaps mozaicism has a part to play in the cause of this. Perhaps the abnormal cells are part of the non foetal pregnancy, or the mozaicism involves a less crucial part of the child. Certainly mozaicism poses real problems about diagnostic certainty, and many mosaic tests have normal foetuses.7 Whatever the reason for this finding, even chromosomal abnormalities, alleged on amniocentesis, do not mean the child will necessarily have the chromosomal syndrome.

Foetal medicine centres

Intrauterine foetal surgery is also able to offer benefits. For example, urinary tract obstruction, can be treated to save renal function. These more simple procedures have a foetal loss of 8- 10%, which may sometimes be justifiable. More complex surgical operations, which are done between 24 and 30 weeks, involve a Caesarean-like delivery, operating on the baby and then returning him/her to the womb. This involves a foetal loss of up to 50% and also risks for the mother. These latter interventions are still rare and experimental.8 The centres are high technology, specialised places, where babies lives can be saved for example in rhesus-type blood problems and where amniocentesis, foetoscopy, and umbilical cord blood sampling and exchange can all be required to save lives. Nonetheless, hearing the 21 week scan described as an anomaly scan, rather than a well-being scan, raises concern as to the motives of such centres. Reading their literature, I fear that they may select out more babies than they save. Much of their expertise was gained by practising on pregnancies due for abortion, some- thing from which we can derive little comfort. I think mothers should be well informed if they need to use their services.

Psychological effects of screening

Modern medicine has many benefits. We are fortunate, in wealthy countries, to have access to such care. Such opportunities have their problems as well. Some people may feel it appropriate that they should have comprehensive knowledge to prepare themselves for the birth of a child with an abnormality, even though there is rarely any significant medical benefit to be gained. On the other hand the distress and disruption of normal pregnancy by worry is widely recognised. Amniocentesis results take two (worrying) weeks to return. Scans may be happy events, worrying, or devastating. It does not take much imagination to consider how this affects the unconditional love of parenthood.

Soft ultrasonographic markers have been suggested to do more harm than good.9 Parents undergo testing for reassurance that everything is alright. Doctors screen for abnormality. Medical success in detecting abnormalities leads to such severe distress that many have questioned the value of such tests.10,11 Worries can be persistent and can damage parental relationships long after birth.12 An abnormal early scan of a baby with severe structural abnormalities will obviously produce great distress. I have seen a mother in a scan room put in this position. Sometimes errors are made in the interpretation of what has been seen with the result that normal babies are aborted. Worst case scenarios are often presented along with comments such as "you must think of the rest of the family". The majority of severely abnormal babies miscarry by the end of the second six months. Kelly13 has beautifully described how precious short lives can be. "To me my baby was lovely". So spoke a mother who 24 hours earlier had given birth to a baby with multiple abnormalities and who died 20 minutes after birth. Thus, continuing to birth may have great benefits. There is evidence that women aborting abnormal babies resolve their grief less well,14 while those who continue to natural outcomes report positive effects.15 Those aborting, therefore, appear to suffer even more than others (perhaps they are a slightly different group to start with). When parents have a handicapped or disabled child, there can sometimes be a sense of embarrassment at the perceived imperfections in the child. How much more so when ante- natal technology claims to be able to spare them such problems? We must remember that the child is an individual of their own right who might one day become embarrassed about their own parents. There is no test predictive of adolescent problems or many other of the most difficult problems that parents and children face.

Ante-natal user experiences

Perhaps examples of my own experience would be helpful at. this point. I trained as a doctor at King's College Hospital, London which has for many years been in the forefront of ultrasound investigation of the unborn and research to decrease foetal mortality. As a result, I have been able to understand all the investigations and stages of my pregnancies. In one pregnancy, during which I had threatened to miscarry several times in the first 3 months, I was told by the obstetrician that I should have the Alpha feto- protein test. I replied that I did not want it: she understood why but still felt the need to press the point. In the end I said that she could do it if she wanted to on condition that I was not to know the result (I had had enough stress by then!). She actually realised that the test was probably unnecessary and unreasonable, and may well have given a false positive result because of the previous problems.

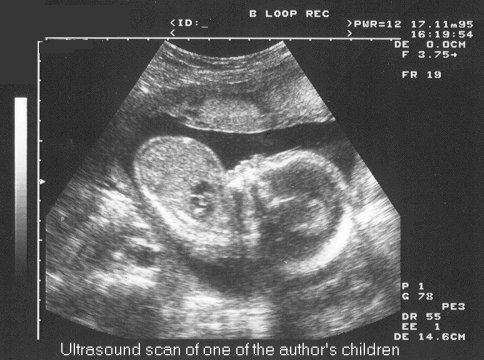

In a more recent pregnancy, I was probably one of those investigated in a large multi-centre study to pick up signs of Down's syndrome using ultra- sound. I was following the progress of the scan when I noticed the ultrasonographer was spending a lot of time viewing round the back of the baby's head. "I'm just measuring fluid around the back of the neck' was the not unreasonable response to my question. It was only after the birth of my baby that I was fully informed of what was being measured and studied. I got my answer from the obstetric registrar whom I met in the car park as we were leaving hospital! Subsequent realisation of how close I had unwittingly been to the receipt of rather non-specific and entirely unconsented information, has made me extremely wary of ever attending for an ultrasound test prior to the time when the information gained is of use regarding the baby's wellbeing.

As a medical student I saw another woman who had spina-bifida herself as a child, pressed to have detailed scans of her child to look for any possible anomaly even though it would not have affected the delivery and even though the mother would not have considered an abortion.

One woman asked me if, by refusing scans, she was really being irresponsible and denying her baby the best chances of being born healthy. In a previous pregnancy, she had lived through the traumas of two weekly detailed scans at a foetal medicine centre to which she had to travel from mid pregnancy. This had been a practical hardship, as she still had to care for the family, but also a massive disturbance to her serenity. The tests had not made any difference to the management of the pregnancy. The obstetric registrar felt that she should go through this process again and, when she refused, wrote in huge red felt pen on the front of her notes to the effect that she had refused medical advice and was highly irresponsible. These were the notes she had to endure everyone seeing each time she attended for care: a gross infringement of personal liberty and autonomy. She did have a detailed scan later on with a view to plan for delivery, but it would be fascinating to know, had she been in a position to press the registrar, exactly what, other than a process leading to abortion, she was refusing.

I know of many women who now fear ante-natal care. They are afraid that doctors will do tests which will show an anomaly and press them to have an abortion: these fears do not seem irrational. They are based upon the experience of earlier pregnancies. Most women simply trust the system, go along and get swept away when an anomaly is found. Even good Christian women who are against abortion seem highly vulnerable to this effect.

The moral nature of ante-natal information

Many would say that ante-natal information is morally neutral and that imparting such information is simply giving parents knowledge upon which they can base their own decisions. In other words, the doctor performing such tests does not become morally part of an abortion if such follows from the test. In one sense this is indeed true. The "smoking gun" is seen at the time of abortion and not ante-natal testing. On the other hand tests, which serve no purpose other than enabling the destruction of handicapped children, may be seen as loading that gun. The distress and worry which follows on from an abnormal result can be used to propel vulnerable people towards decisions which they would never otherwise have considered. The mere availability of such information appears to have conferred, for many, a duty to have the tests and abort the abnormal children. Too often I have heard people using financial and emotional arguments to criticise those who opt to keep a baby despite knowing that it is handicapped. Many talk of the reassurance that normal tests can provide for parents. In fact this is probably a deception. Scans can never identify normality. They can only detect or fail to detect anomaly. The effort that goes into aborting abnormal babies generates a conditionality about pregnancy which implies and persuades mothers that disabled children are less human than others.

Morally therefore, ante-natal testing, which is purely for anomaly finding, may not be licit. Indeed such tests may he the preparatory work for promoting abortion. As usual, knowledge is a mixed blessing.

What should we do?

We cannot ignore the tragedies that are currently occurring as a result of ante-natal screening. There is real need to support mothers in pregnancy. They are often alone as they deal with these issues on a personal level. They need to know of the risks and issues associated with ante natal testing. They also need to know where to get support and help. We need to work hard to ensure that there are good, well informed pro-life Christian obstetricians and GPs to whom such women can turn for help. We need to be able to do so with the support of a deep faith and spirituality which clearly understands the human- ness of the unborn child as well as the humanity of the mother, especially the mother in distress.

Summary

Since ancient times, men and women have sought to discern their future. More recently in 'The Imitation of Christ', Thomas A Kempis (14th century) encapsulated the unnecessary disturbance of serenity we may allow ourselves to be prey to by unnecessary enquiry into future conditions for which there is currently neither a moral nor effective remedy. In book 3, Chapter 30 he writes

"What doth solicitude about future accidents bring thee, but only sorrow upon sorrow? Sufficient for the day is the evil thereof (Matt. vi, 34). It is a vain and unprofitable thing to conceive either grief or joy for future things which perhaps will never happen ..... For he [the devil] careth not whether it be with things true or false that he deludeth and deceiveth thee; whether he overthrow thee with the love of things present or the fear of things to come. Let not therefore thy heart be troubled, and let it not fear."

References

- Shackley P. McGuire A. Boyd PA. Dennis J. Fitchett M. Kay J. Roche M. Wood P. An economic appraisal of alternative prenatal screening programmes for Down's syndrome. Journal of Public Health Medicine. 15(2):175- 84,1993

- Dyer C. MOD settles over Down's syndrome child. BMJ 314: 1368. 1977.

- Makrydinas G, Colis D. NueM Translucency. Lancet 350: 1630-1 1997.

- Hyett JA. Sebire NJ. Snijders RT. Nicolaides KH. Intrauterine lethality of trisomy 21 fetuses with increased nuchal translucency thickness. Ultrasound in Obstetrics & Gynaecology. 7(2) 101-3, 1996

- Salvesen DR Goble O. Early amniocentesis and fetal nuchal translucency in women re- questing karyotyping for advanced maternal age. Prenatal Diagnosis. 15 (10):971-4, 1995

- Gravholt CH Juul S. Naeraa RW. Hansen J. Prenatal and postnatal prevalence of Turner's syndrome: a registry study. BMJ. 312(7022):16-21,1996.

- Johnson A. Wapner RJ. Mosaicism: implications for postnatal outcome. Current Opinion in Obstetrics & Gynaecology. 9(2):126-35, 1997.

- Kimber C, Spitz L, Cushieri A. Current state of antenatal in utero surgical interventions. Archives of Diseases in Childhood. 76: F134- F139 1997.

- Whittle M. Ultrasonographic markers of foetal chromosomal defects. BMJ 314: 918, 1997.

- Bunn A, Joennou G, Forrest K, Rea R Serum screening for Down's syndrome. BMJ 312: 974,1996.

- Warner D. Testing for Down's syndrome causes too much stress. BMJ 312: 379, 1996.

- Mason G, Baillie. Counselling should be provided before parents are told of presence of ultrasonographic markers of fetal abnormality. BMJ 315: 189-90, 1997.

- Kelly J. A difficult delivery. Lancet 335: 861, 1990.

- New England Journal of Medicine 326: 1217- 1219,1992.

- American Family Physician 1992, Vol. 45 p. 137-140.

Dr. Josephine Treloar is a GP practising in Kent.